Depositors Disciplining Banks: The Impact of Scandals

Can depositor activism make a real difference? New research set to be presented at the upcoming Stigler Center Political Economy of Finance conference examines the Dakota Access Pipeline controversy and similar events and suggests that banks see significant decreases in deposit growth after experiencing environmental, corruption, and tax evasion scandals.

In April 2016, the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL) protests began in reaction to an approved oil pipeline project in the northern United States. The pipeline sparked controversy among environmental activists as well as Native Americans, as it was intended to cross the Missouri and Mississippi rivers as well as ancient burial grounds. What was exceptional about this incident was not just the sheer scale of the on-site protests, but also the rather immense financial coordination among activists. By February 2017, over 700,000 people had signed one of six petitions addressed to banks financing the DAPL. Individuals who signed the petition collectively reported having over $2.3 billion invested in these banks through checking, mortgage, and credit card accounts. They threatened to divest their wealth if the banks continued financing DAPL and by then, thousands had reportedly closed their accounts, removing over $55 million.

Did Money Follow the Words?

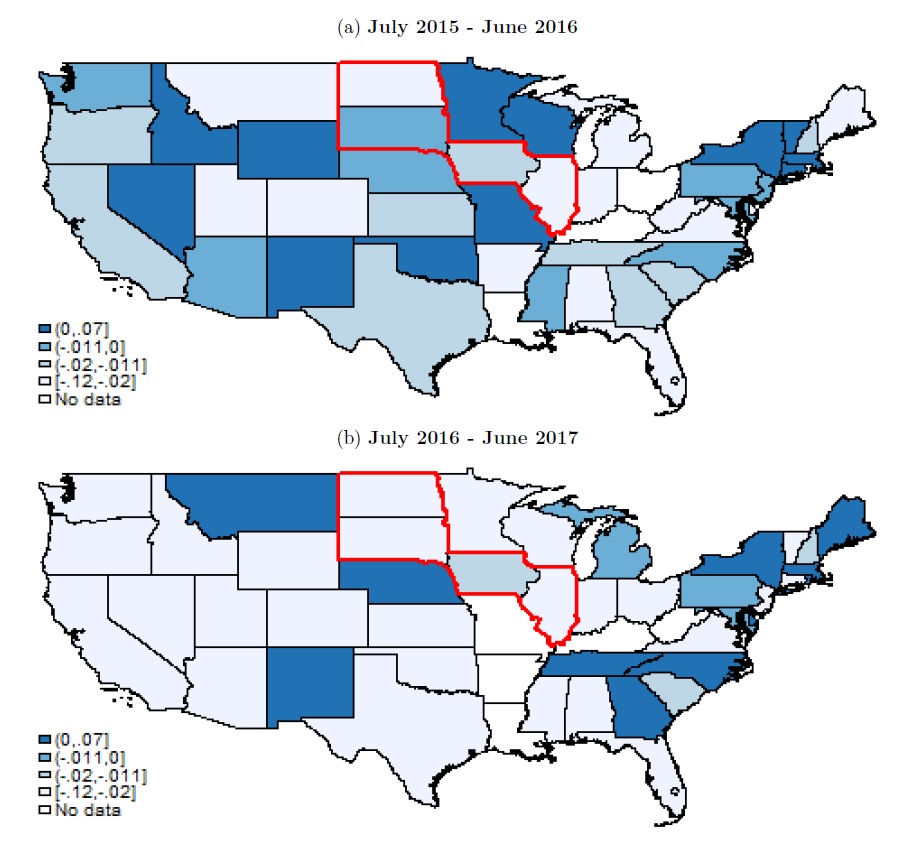

To test the true extent of this depositor movement, a new study utilizes the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) summary of deposits data, which provides branch-level data for over 100,000 branches across the United States. In total, 17 banks directly financed the construction of the DAPL; among them, the banks that had a significant branch-level presence in the United States were Citigroup, Bank of Tokyo Mitsubishi UFJ, BBVA, BNP Paribas, SunTrust Robinson Humphrey, TD Bank, Mizuho Bank, SMBC and Wells Fargo. These banks had nearly 11,000 branches across the United States and were collectively known as the project financing banks, which received much of the initial public attention. The heat maps below give clues to the extent of the depositor momentum. Shades are based on the performance of DAPL financing branches: the darker the color, the better these banks were doing in terms of deposit growth. Before the banks were targeted by protesters (i.e., July 2015 to June 2016), DAPL branches were doing relatively well across the United States, with many having on average between zero and 7 percent higher deposit growth rates compared to other branches within the same state. However, once the bank protests started (i.e., July 2016 to June 2017), DAPL branches across America started experiencing lower than state average deposit growth rates. It seems, via the depositor activism channel, the DAPL protests had truly become a nationwide phenomenon.

Notes: The heat maps are created by utilizing over 100,000 FDIC-insured US bank branches for 2016 and 2017. Areas highlighted in red represent states that include the Dakota Access Pipeline. Darker colors indicate that DAPL branches had higher than state average deposit growth rates, while lighter colors mean they had lower than state average deposit growth rates. The peak of the DAPL scandal was in 2017 and the results demonstrate that on average, across the United States, DAPL bank branches turned lighter. This means that the deposit growth rates of these branches were on average lower compared other branches of each state.

How and How Much?

While reliable estimates are hard to come by, the initial findings indicate that these deposit withdrawals amounted to as much as $8-20 billion dollars for these banks. This is by far no surprise as branch protestswere taking place across the United States and even globally. In certain cases, branches had to close down for the day and some people went as far as chaining themselves inside the branches in a show of solidarity with the protesters in North Dakota. Not all protests were local: major events took place all over the country, including at the U.S. Bank Stadium in Minneapolis, Minnesota. During an NFL game between the Vikings and Chicago Bears, protestors hung a large banner from the roof of the stadium demanding U.S. Bank divest from the DAPL. But what motivated people to move their funds? Further examination of the data suggests that these effects were stronger for branches in pipeline states, demonstrating that depositor movement was heavily influenced by people’s actual proximity to the scene of the controversy. By incorporating data from the Yale Panel for Climate Change Communication and county-level measures of social capital, early findings indicate that county-level attitudes towards climate change and social capital also had an influence on people’s propensity to move their deposits.

Where Did the Money Go?

Preliminary findings suggest that savings banks, which tend to be more localized institutions with relatively more transparent asset allocations than commercial banks, were among the main beneficiaries of this unanticipated depositor movement. The results show that this effect was exceptionally strong when savings banks were located in counties with proportionally more DAPL banks. This finding is not surprising: while these institutions in general benefit from their reputation and overall business focus (e.g. more locally focused investment strategies), NGOs quite often specifically instructed their petitioners to move their money to smaller and more local institutions, including savings banks and credit unions. For these banks, it literally paid to be good.

Did Any of This Make a Difference?

In the end, the pipeline became operational despite major backlashes. However, the event was not without its financial consequences. Major banks, including ABN Amro and ING, were quick to make public statements as a reaction to the pipeline scandal. They publicly re-evaluated their commitments to the project and by March 2017, ING sold its stake in the DAPL loan. Other banks, including DNB and BNP Paribas, soon sold their stakes as well. As public pressure further increased, outrage was not only aimed at those financing the pipeline directly, but also those who provided corporate financing to the pipeline companies.

As time went on, the city of Seattle cut ties with Wells Fargo, the city of Los Angeles moved to divest from Wells Fargo, the city of San Francisco moved to divest from companies financing the DAPL, the Norwegian wealth fund stated its intent to drop fossil energy investments, and numerous Norwegian pension funds divested from companies behind DAPL. Furthermore, US Bank stated its intent to stop financing future pipeline projects (though this was later retracted) and the Scandinavian bank Nordea decided to exclude three companies behind DAPL, which was partially due to the pipeline companies’ unwillingness to talk about these events.

Interestingly, the pressure on banks did not peak in 2017. Protests continued and with an even broader focus, e.g. with the inclusion of Tar Sand projects and Keystone XL. The project financing banks are still being targeted and more banks have been included in subsequent petitions. NGOs have reported that activism continues and there have been no signs of these protests stopping. As recently as March 2018, after major public pressure, Citizens Bank withdrew from a loan aimed at financing one of the pipeline companies involved in the DAPL.

Was This A One-Off Event?

How much should we really care about this, and how likely is it that this would ever happen again? Further findings from the study suggest that this channel of depositor discipline is a much more general phenomenon than the DAPL protests. By using global, quarterly bank-level data and a hand-collected dataset on bank-level scandals, results from the study show that total deposit growth decreases when banks are involved in tax evasion (e.g., Panama Papers), corruption (e.g., Libor scandal), and environmental scandals (e.g., the Carmichael coal mine project in Australia). It seems DAPL was by no means a one-off event. The term depositor discipline has begun to earn itself a whole new meaning.

The banking sector has been regarded as a major contributor of financing for the real economy and therefore a crucial value-adding mechanism for the financial system. In the recent decade, however, the banking sector has been under scrutiny. To this day, banks continue financing major coal and carbon-intensive projects that undermine the Paris Agreement’s aim of limiting global warming to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels and they have further been identified as some of the largest enablers of the $21 trillion to $32 trillion of private financial wealth invested in tax havens. Could depositors perhaps make a difference?

Mikael Homanen is a PhD Candidate at Cass Business School in London. His research focuses on the intersection of externalities and financial markets with a further focus on banking and investor ESG (Environmental, Social & Governance) policies.

This blog was originally posted on Promarket.org. View the original here.